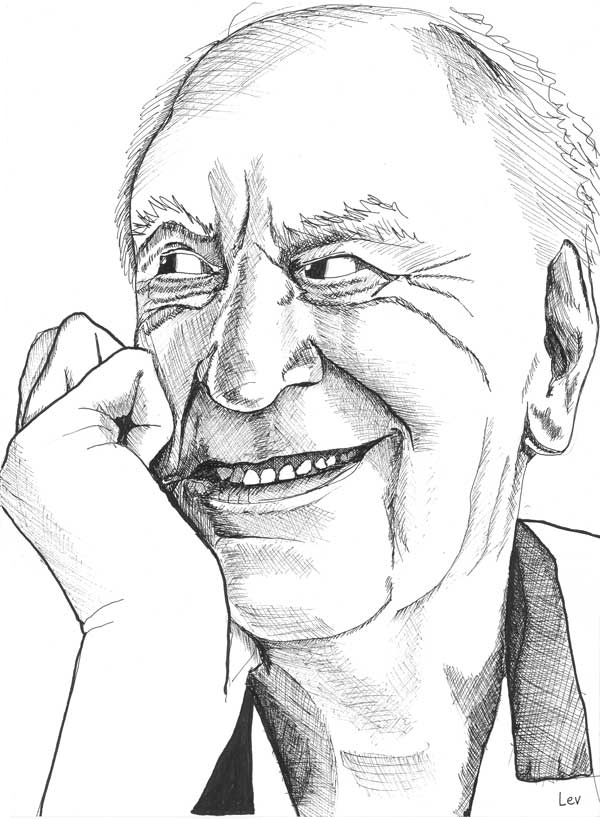

LEV: “ With every loss there is a gain, and contrariwise.”

His story challenges the stereotypes of memory as solely an intellectual process and memory loss as an inevitable part of aging. And I realize the depths of my denial and suppression of the sensory in my life and wonder what force of will “ keeps me going”.

Brush in Hand: Lev’s Story

Walk up the gravel road past the four corners where the church, the post office, the Monhegan House Inn, and the general store meet. The road narrows, the stones are bigger, ready to trip over; wild roses fence in houses on either side. There’s a big red-painted house on the left as you turn a corner, and on your right a sign points up a hill to the hostel. That’s the last building you’ll see before the painter Wyeth’s house, high on a cliff looking over the ocean and the rusty-ribbed shipwreck keeled over near shore.

For three precious weeks, Lev stays in a cottage at the island’s hostel, weathered white clapboard with a green peaked roof down a grassed hill from the main building, closer to the coast road and the sounds and smells of the sea – black-backed gulls wheeling and crying overhead announce the fishing boats he loves to paint coming into harbour. Because of a serious heart condition, Lev stays in the only ground-floor room, with access to the staff toilet and laundry. Every evening, painters gather around the fireplace in the parlour across from his room to critique each other’s work. Bystanders, which I often am, are welcome to listen, but not to talk. Lev is always in the thick of it, a stocky, muscular man, white-haired, with tan lines wrinkling around his gleaming brown eyes as he laughs or makes a point. Loving every minute.

Lev was a linotype operator with the NY Times and took up painting later in life as a way to be with people “who are more likely to go out on a limb and take chances”. His paintings are very different from the representational and abstract work on the island (or anywhere else, for that matter). Responding to his gut reaction, he takes the idea of what he wants to paint from the scene and renders it in a combination of bold shapes, vivid colours, and striking patterns that hang together so incredibly well that they have an immediate, and irresistible, sensual appeal.

I comment that he describes the way he paints in the same way that he’s told me how he remembers events: once he has a key word, he sees the scene as if it’s unrolling right before his eyes, and then he picks out the details he wants. In painting, his gut reaction to what he sees or remembers is like a key word: it summons and organizes what he expresses on a canvas. He replies that I may have a point, although he’s never thought about it that way, because he doesn’t think painting is really about memory. “I’m experiencing something.’ The technique is learning how to express the feelings.”

He never forgets the feelings that drive the paintings. “Once I remember, once I have the incident, or the image of where something was, they all come back as if they’d just happened.” But the idea that memory is more than an intellectual process, can live anywhere else but in his mind, still bothers Lev. One day we were having a conversation with Meyer and Miriam, also long time summer residents. Lev was stoutly maintaining that he made sketches from his imagination, “and that isn’t memory.” Meyer asks him how he does this.

“Well, I think about how a fisherman looks, how he feels when he is casting a line, and will experiment in the sketch until I get the line of the shape I am picturing.”

“So you are remembering that, how he looked, how he felt?” Meyer asks.

“Yes, but it’s not just memory. I remember how he looks, and I am feeling it when I am painting it.”

“So, you put it together, some image you remember, and when you’re remembering it, the feeling comes up, as if you were there.” (Meyer was relentless when he wanted to track something down.)

“As if I were there now,” Lev insists. “It’s a two-way street. Whether I am remembering it, or when I am right there seeing it, it speaks to me in the same way: I feel it, and then I try to express it, to paint it.”

“So, it’s like you have a mind memory and a gut memory, they both bring out feelings that you paint,” says Meyer. Lev throws up his hands, says he doesn’t really care what anyone calls it, he’ll keep on painting the essence, wherever it comes from.

One day I ask him why he never paints hands, and he laughs, telling me that he can’t make hands look the way he wants, so he finds a way to leave them out: ever the iconoclast. “Rocks I can paint, but not hands,” he says, “because I can imagine how a rock feels, standing there alone, heavy, hardly able to move — although they do move, the geologists say, even breathe, and the waves change them, over a long time.” With hands, he thinks it a matter of a technique he’s never mastered, because he is more preoccupied with getting the line of the shoulder and of the arms straining as they pull in the weight of the nets.

“You can feel that straining?” I ask him.

“Oh, yes, I’ve done plenty of fishing, I know just how it feels in my arms and shoulders. You can’t forget that kind of thing.”

Forgetting names and dates and an occasional appointment were minor details for Leo compared to his heart condition and its increasing effects on his mobility, which he found suffocating. Being with interesting people and getting out — into nature and away from his meagre Brooklyn surroundings — have always been a vital part of what he needs because he thinks he can never paint at home, alone. “If I can’t get out, I won’t have the quality of life I want, and if I don’t have the quality of life — that’s it. I’m out of here.” Although he has hated hospitals and doctors ever since his wife and daughter died, he finally agreed to a coronary bypass after a friend’s had given him a new lease on life. Lev had high hopes, but the operation was only partially successful. He still has to take diuretics and other medications, still can’t walk far, particularly in cold weather.

But Lev had a surprise coming. In a letter he wrote me he said “I am amazed at how my painting is improving all the time. I’ve been functioning very poorly and have not been moving around so much, so have been doing more painting. All these years I’ve never been able to paint when I’m at home alone. My painter friends visit me, and we look at what I’m working on, but we can’t paint together, there’s not enough room to swing a cat. But being housebound and alone so much, my deterioration has had a beneficial effect by my starting to paint when at home! All there is left to do is paint.

“And surprisingly, as my body keeps falling apart and rotting, my painting is improving by leaps and more leaps — and it amazes me that while I can hardly work for more than twenty minutes without getting pooped, my painting is zooming, both design-wise and colour-wise, the feelings come pouring out. With every gain there’s a loss and contrariwise. I haven’t enough energy to carry a half a gallon of milk, but I can still push a brush around, and I’m able to achieve on canvas more than ever the concepts — scenes, people etc. — I have in my head. I know my painting is me”

Isadora Duncan was Lev’s “Mother Courage,” and Lev is mine. Years after he died and when multiple health problems were besieging me, all I had to do to “put me on the up elevator again”, as Leo would say, was to think of Lev painting his feelings, his exuberance triumphing over pain — not forcing anything, but having the patience to wait, to let the “juice of life” flow. And it wasn’t just physical pain that he vanquished. Whenever I look at his canvasses, I remember how facing the fears of isolation and invisibility that come with chronic illness ended up giving him the intense, and completely unexpected, pleasure of becoming better and better at what he loved to do most and had thought he could never achieve alone.