MEYER: “Are you learning something? Nature is my teacher now.”

I learn that I value intellectual excellence at the expense of sensory experience and how loss can bring these worlds together in a renewed sense of community.

Meaning and Sensory Memory

I heard Meyer before I met him, playing piano at one of the island’s evening singsongs. Hunched over the keyboard, head jutting forward in concentration, his long bony legs are clad in narrow black trousers, and his elbows are thrust up on either side so that his sweatered arms are like wings unfolding. He shoots a quick, quizzical glance over his shoulder as his fingers ripple a change in the music from his own composition to one that the audience, sitting in chairs or cushions around the fire, can sing.

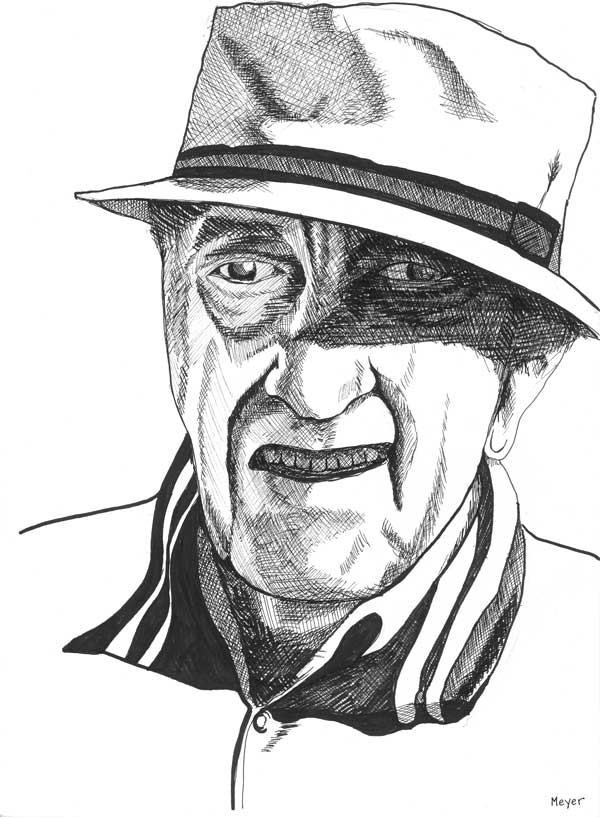

I often met him on the island’s only road — tall, gangly, sporting a pork-pie hat over a fringe of grey hair. He needed a leg brace and walked with a cane, limping a little, a shopping bag in his other hand, looking around as if he were seeing the houses and gardens for the first time. Often he talked intently to someone, bag on the side of the dirt road, gesticulating with his free hand.

Meyer’s father was a singer, his mother a painter and he grew up steeped in the sensory worlds of music and painting. He became a professional musician, “earning a living at anything and everything, from pianist in the pit for silent movies to accompanying soloists and string ensembles.” Growing up he felt different, isolated from his peers, and lonely, until he saw a woman polishing the one window remaining in a bombed-out building in Europe when he was in the U.S. armed forces. Meyer says, “I can still hear the squeak of the rag, her eyes staring ahead, not looking at the marching troops or the tanks rolling by.

“Why was she doing that? The building was wrecked; no one could live there. It seemed useless, but she was trying to make some meaning out of her life by doing something familiar … It came right down to their daily life and what that meant and how much we didn’t know about any of it. We had no understanding, no sense of what they’d been through and would go through for years … From then on, all of my life has been a search for meaning — in my own mind, in reading, in listening to other people, in any way I can.

“… I’m not knocking wanting to feel secure. Who doesn’t? It’s a chaotic world out there. But the big question is how a person makes a meaningful, liveable existence in a world that could blow up tomorrow. This planet could blow up anytime. That’s a fact. I can’t shut that out. She would need to shut it out for a while, just to be able to deal with such horror. But so many people today are living all the time by shutting out. Escaping. I think the greatest gift we have is consciousness, and I feel good whenever I understand something, and grateful … Living or dying, you need to know what’s going on in you to be able to cope with the world … You have to put your emotions, your likes and dislikes, personal gratification and so forth, on the back burner, so you’re not run around by your conditioning. Then you can see something … Only human beings make meaning. … Awareness is like a light. You’re in a room, and all the shades are down. You raise a shade, and you can see more clearly, and there’s the kind of pleasure you feel that goes with wisdom.”

As he ages Meyer feels “as if there is a kind of brotherhood of seeing. People are like passengers on a ship passing one another in the dark and waving to each other in this journey through the fog that is life. I’d wave to somebody who has overcome fear or cowardice, to someone who is looking for the truth.” Although he realizes that “there are not many takers for this kind of journey,” travelling it has taught him that, after all, “we are not alone.” And so for him, memory is important as a record of the past and for connecting to other people, as well as to keep on learning. He knows (as Mae and many of the others do) that he must be open to the “language of the young” to learn, and to stay connected in a culture that tends to deny aging and the value of the old.

With increasing deafness Meyer must find other ways than hearing and music to keep on learning and to connect with the physical world. in sensory awareness classes on the island he learned another language, and that “the parallel grooves (body and mind) of the universe must interact.” With age, the sensory becomes more important, but it’s also more difficult, because you must train the less dominant senses to be more acute so that you can find ways to “make the world fresh … We work on it, we keep on reminding ourselves that no sensation is ever the same, that walking down the road today is not the same as yesterday. If you don’t, you’ll find yourself saying, ‘What the hell, I’ve done that so many times.’ And then you’ll start to forget. Especially if it’s harder to do — which it usually is.”

Sensory memory is also a way to stay connected with others through vicarious experience, and is an important means to override the physical and emotional pains of aging.

“I can say, ‘I want to walk through this world in a semi-daze, waiting until the end,’ like so many people who are old. Or I can adjust, remember the things I used to do with a kind of empathy, and enjoy those memories by entering into them imaginatively.”

Meyer thinks that older people have an advantage in this kind of “vicarious enjoyment,” because they can “draw on a lifetime’s experience to enter into the state of another person — a ballet dancer, or even a bird or a tree — so that you’re not just sitting there watching them move, you are dancing with them. You may not be able to do much; more than likely you’re not. But you can appreciate it … get some kind of gratification out of watching beauty in motion … or remembering experiences that have moved something in you … I feel the survival of the universe depends on that.”

Meyer had no illusions about the debilitating effects of illness, poverty, and social rejection. He knew that such conditions make it very difficult to appreciate the gift of life, figure out what we can still offer as we age, and grasp all the wonders of the universe around us. The indomitable spirit that kept him going is one of my beacons and I’m pretty sure we would have a good time arguing about how to find the words to include women in the “brotherhood of seeing.”